Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a pregnancy condition characterised by extreme levels of intractable nausea and vomiting, fatigue, distorted olfaction responses and hypersalivation. Symptoms can lead to dehydration, malnutrition, and secondary complications such as Wernicke's encephalopathy, oesophageal tears, hypocalcaemia and thyroid dysfunction (Dean and Gadsby, 2013; MacGibbon et al, 2015).

An estimated 30% of pregnant women suffer high levels of morbidity from nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (NVP) without receiving a diagnosis of HG (Gadsby and Barnie-Adshead, 2011a). Symptoms of NVP appear on a spectrum ranging from normal to severe, and HG is considered to be at the extreme end of that spectrum, affecting 1-1.5% of the pregnant population (Einarson et al, 2013), and accounting for approximately 25 000 hospital admissions annually (Gadsby and Barnie-Adshead, 2011b).

As yet, there is no internationally agreed definition of HG distinct to NVP (Painter et al, 2015; Grooten et al, 2016). The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) have suggested criteria for diagnosis that includes admission to hospital, weight loss of more than 5% and clinical signs of dehydration (RCOG, 2016). However, women with severe symptoms who do not fit the criteria, or who meet barriers to accessing treatment, may still experience significant psychological distress and mental health effects (Dean and Murphy, 2015).

Despite recognition of the severity of symptoms, the negative effects on women's lives can sometimes be underappreciated by health professionals, social workers and the general public (Sykes et al, 2013; Dean and Marsden, 2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis in 2016 found a significantly higher rate of depression and anxiety in women with HG compared to controls (Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017). While the association between HG and depression and/or anxiety has long been recognised (Munch, 2002a), the directional relationship has been controversial and, historically, mental ill-health has been cited as the cause of HG rather than the result (Fairweather, 1968). In part, this may be due to the as yet unknown aetiology of the condition, which is likely to be multifactorial and almost certainly contains a genetic element (Fejzo et al, 2008; Mullin et al, 2016). This has resulted in misguided approaches to treatment for HG, such as enforced isolation and psychological interrogation, which was endorsed as recently as 2004 (Karpel and de Gmeline, 2004). A review in 2016 found that the enduring stigma surrounding the condition negatively affected the treatment some women received and could lead to terminations of otherwise wanted pregnancies (Dean, 2016). Furthermore, it found the disproven psychiatric origin theory remains an inhibitor to the empathy and care that the condition deserves (Fejzo and MacGibbon, 2012; Dean 2016).

Medical treatment for HG has seen significant improvements in recent years, and guidelines advocate early aggressive treatment of NVP to reduce the risk of hospital admission for HG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2015; RCOG, 2016). While treatment guidelines help women to receive the available treatments in a timely manner, the efficiency of the treatments is often insufficient for HG and many women find little to no benefit from the currently available anti-emetics (Boelig et al, 2016). No ‘cure’ is available and treatment serves only to palliate the symptoms until they naturally improve either during or after the pregnancy. It is for this reason that the Mitchell-Jones et al (2017) review calls for an urgent shift in care and treatment to holistically appreciate and address the psychological symptoms caused by HG.

In order to address and offer supportive treatment for the psychological morbidity caused by HG, an understanding of the effects of the condition on women's lives is required. Such effects cannot be easily identified from a meta-analysis of quantitative depression and anxiety scores. Rather, an exploration of women's experiences is required. The following literature search was undertaken as part of a wider project looking at the effect of HG on women's reproductive lives. The results in relation to mental health are reported here, however searches were not limited to mental health. As pregnancy sickness appears on a spectrum of severity, with HG at the extreme end, searches were not limited to HG and included milder degrees of NVP as categorised within the studies.

Methods

The search, conducted in November 2016, used the Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research type (SPIDER) strategy, developed by Cooke et al (2012), to maximise the rigour of the search and ensure all relevant publications were revealed.

Search strategy and exclusion criteria

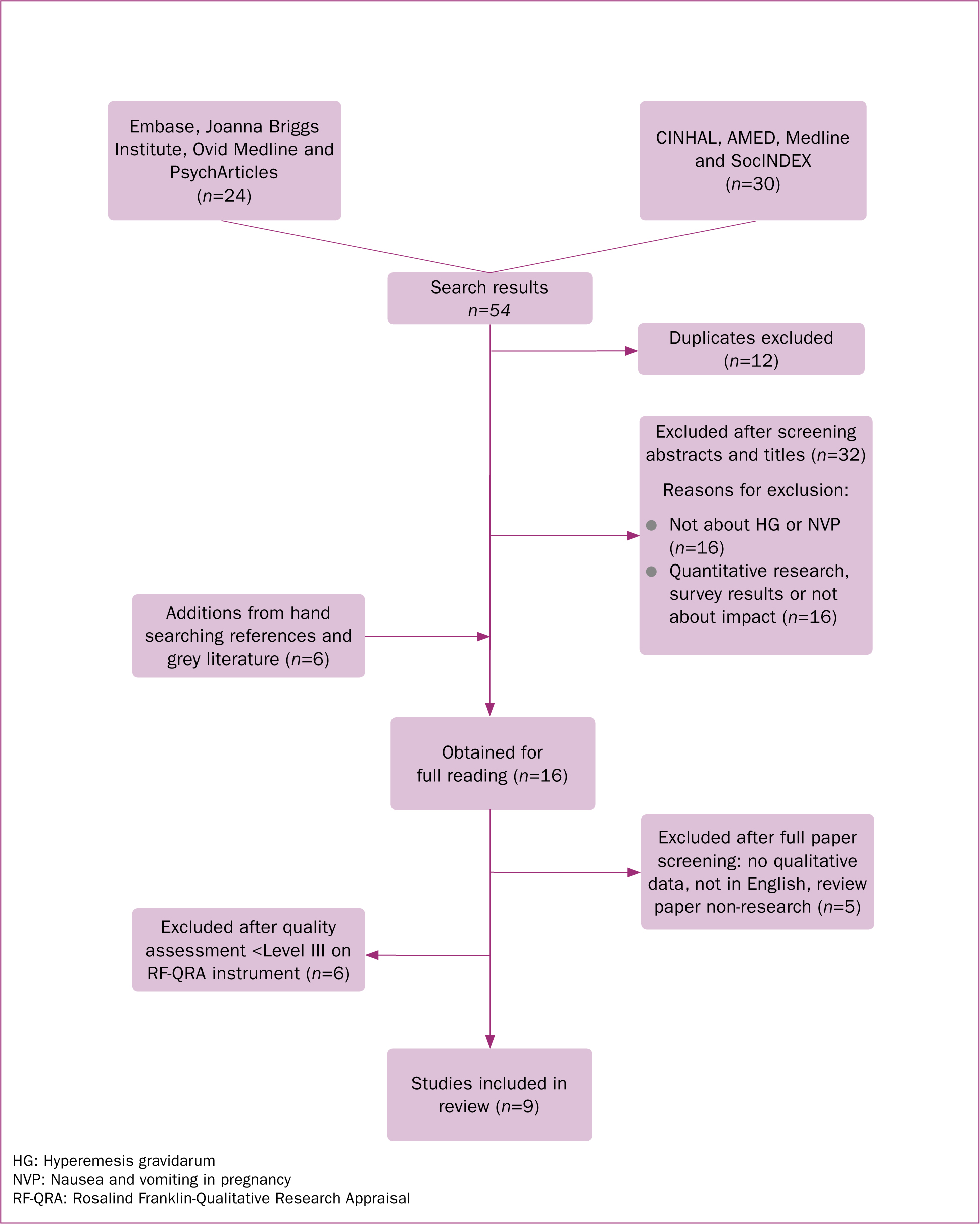

The following key terms were developed via SPIDER and linked with Boolean operators: (hyperemesis gravidarum OR pregnancy sickness OR nausea vomiting pregnancy) AND (impact OR quality of life OR mental health) AND (experience OR perceptions) AND (interviews OR focus groups OR lived experience OR observation OR survey OR case study OR qualitative OR narrative). The databases AMED, CINAHL, Embase, Joanna Briggs Insitute, Medline, Ovid Medline, PsycArticles, SocINDEX were searched. Figure 1 outlines the findings from the search strategy. No date limitation was initially applied; however, all results were published in the last 25 years and assessed to still be culturally and medically relevant. No language restrictions were applied during the initial search.

Further exclusion from screening

After retrieving the full text publications, articles were screened using the following decision rules: ‘Is the research peer reviewed?’ and ‘Is the problem researched important to the review question?’ (Henderson and Rheault, 2004).

Assuming these questions were answered positively, then four further screening criteria were applied, and studies that did not meet them were excluded from further analysis. The screening criteria asked whether the inquiry process involved observation of social or human problems in a natural setting; interpreted the observations; tied the observed phenomena to understanding, explanation or theory development; and met ethical standards. Following the application of this screening process, one quantitative quality of life survey (Munch et al, 2011) and one review of quantitative quality of life studies (Wood et al, 2013) were also excluded. Additionally, one article, which was a general review of existing literature,(Soltani and Taylor, 2003), and one publication that was a self-reported narrative was excluded (Dean, 2014). Only one non-English publication, a Taiwanese study (Cheng and Chou, 2008), was identified and as resources were not available to translate the publication, it was also excluded.

Quality assessment

A total of 11 publications were quality assessed using the Rosalind Franklin-Qualitative Research Appraisal Instrument (RF-QRA), as detailed by Henderson and Rheault (2004). The RF-QRA assesses four aspects of trustworthiness in order to establish a level of qualitative evidence similar to Sackett's levels of evidence, which are typically used in quantitative research (Henderson and Rheault, 2004). The four aspects of trustworthiness are credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability. The level of quality corresponds to the number of aspects of trustworthiness achieved. Publications assessed to be Level I would have all four aspects of trustworthiness confirmed, while Level V publications would demonstrate problems or absences in all four aspects.

Although no guidance is provided by Henderson and Rheault (2004) regarding what level of evidence publications should achieve, for this review, only studies achieving Level III or above were included. Thus two publications were excluded: Poursharif et al (2008), a Level IV study lacking transferability, dependability and confirmability, and Thomas (2004) a Level V study with methodological problems in all four aspects.

Figure 1 , in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting reviews, summarises the findings from the searching and review process and Table 1 outlines the studies included in the final review.

| Study | Country | Purpose and methods | Participants | Analysis | Summary of findings | RF-QFA level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O'Brien and Naber (1992) | USA | To examine, via semi-structured phone interviews, alterations in family, social and occupational functioning due to NVP, and factors that helped or worsened symptoms | 27 women: 5 with severe symptoms or HG, 8 with moderate symptoms and 14 women with less severe or mild symptoms | Unclear how themes and categories were established. Work was part of a larger quantitative project, serving to triangulate the results and describe the experiences | Changes in family, social and occupational functioning were significant and greater for most participants than is generally believed. Resting was the most important factor in managing symptoms. Olfactory and other sensory stimulation and certain foods and drinks intensified symptoms | III |

| O'Brien et al (1997) | Canada | To assess symptom distress and severity over 7 days and evaluate efficiency of symptom relief measures. Symptom and intervention diaries were used to collect data | 162 women over the age of 16 experiencing NVP. 124 completed diaries were returned for analysis | Content analysis by two researchers and one research assistant. Categories and themes reached by discussion until consensus | Many women, particularly those with more severe symptoms reported that ‘nothing helped’. Women altered normal activities, controlled their environment, implemented eating and drinking strategies and used medication. Sensory and olfactory stimulation exacerbated symptoms | II |

| Munch (2002b) | USA | To investigate women's beliefs about the cause of HG, the seriousness of the illness and the effect on their daily lives. Data collected via semi-structured telephone interviews | 96 women hospitalised for HG | The researcher conducted a rigorous thematic analysis using a constant comparative method. Although there was only one researcher, an audit trail was used to safeguard against investigator bias | Women considered HG to have a physiological cause and rejected the notion of psychological aetiology, although stress exacerbated symptoms. HG negatively affected their daily lives and consequences included lost wages and jobs, inability to self-care or maintain a household, and childcare issues. Women reported being expected to maintain their roles as mothers, wives and employees while ill | III |

| O'Brien et al (2002) | Canada | To understand how women cope with severe NVP semi-structured interviews in hospital or on the phone were conducted and one focus group was held | 24 women admitted to hospital for HG. 16 had one interview, 4 had two interviews and 4 took part in a focus group | Rigorous and careful analysis conducted by multiple researchers. Categories determined by consensus and emerging theory was presented to the focus group | Women experienced profound loneliness after needing complete social and physical isolation to cope with symptoms, and reported loss of control over almost every aspect of life and feelings of guilt and helplessness | II |

| Meighan and Wood (2005) | USA | To describe the experience of HG and how it affects perinatal maternal role assumption via interviews | 8 women with HG | The study describes a rigorous analysis process using open and axial coding, and constant comparative analysis | Themes included ‘Struggling with Sickness then Regaining Control and Making Up for Lost Time’, ‘Seeking a Cause, a Remedy, an End’ or ‘Learning to live with it’. HG seriously affected maternal role assumption | II |

| Chou et al (2006) | Taiwan | To gain an in-depth understanding of how Taiwanese women cope with NVP via face-to-face interviews with open ended questions | Purposive sample of 10 women with mild-moderate NVP. Women with HG were excluded | Analysis was in the original language and translated after for publication. Authors state they used ‘Colaizzi's analysis steps’, an approach to phenomological analysis | Four themes emerged: ‘Understanding NVP’, ‘Finding coping strategies’, ‘Psychosocial adaptation’ and ‘Needing support’. Given the women in this study had mild-moderate symptoms, the severity of adverse effects was striking | II |

| Locock et al (2008) | UK | To explore women's experiences of NVP. In-depth narrative interviews were conducted face-to-face | As part of two projects a total of 66 women, 7 couples and 3 male partners were interviewed. Levels of NVP varied from mild to HG. Participants were recruited to obtain maximum variation | Programme data were coded systematically using software and analysed thematically independently by two researchers | NVP appeared on a continuum, from no sickness to HG. Women viewed sickness as something to be expected, survived, resisted, resented and acknowledged. Women felt little control over symptoms and women with more severe sickness doubted they could endure another pregnancy with a child to look after. Women reported that when NVP was worse than expected, it disrupted women's lives | I |

| Power et al (2010) | UK | To describe the experience of HG from women's perspective and explore barriers and facilitators to caring for women with HG with health professionals via in-depth, semi-structured interviews and focus groups with staff | 18 women with HG were interviewed and seven staff focus groups with 60 health professionals were conducted | Line-by-line coding was used to identify categories via the constant comparative method. Key categories were compared with findings from ongoing quantitative study for evidence to support or refute themes. It was unclear how many researchers were involved in analysis | The main themes were ‘The effect and burden of symptoms’, ‘Managing the burden’ and ‘Women's feelings of being unworthy of medical attention’. The researchers found that HG affected every aspect of a women's life and made day-to-day functioning very difficult or impossible. Families and paid employment were also negatively affected. | II |

| Isbir and Mete (2013) | Turkey | To explore how Turkish women experienced NVP based on the ‘Roy Adaption Model’. In-depth face-to-face interviews were conducted | 35 pregnant women with NVP for at least three days. No distinction was made with HG | Careful translation of data occurred. Content analysis was conducted independently by two researchers and presented to three further experts for monitoring | Wide ranging effects on women's physiological state, self-concept, role functionality and social interactions described | I |

HG: hyperemesis gravidarum; NVP: nausea and vomiting during pregnancy; RF-QRA: Rosalind Franklin-Qualitative Research Appraisal

Critical appraisal of the literature

Overall, the quality of the nine publications included was high, with two studies achieving Level I (Locock et al, 2008; Isbir and Mete, 2013), five studies achieving Level II (O'Brien et al, 1997; O'Brien et al, 2002; Meighan and Wood, 2005; Chou et al, 2006; Power et al, 2010) and two studies scored Level III (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; Munch, 2002b). All publications, except the two Level I studies (Locock et al, 2008; Isbir and Mete, 2013), lacked demographic diversity, and all Level II studies highlighted this when trustworthiness was discussed. The only study to adequately address transferability was by Locock et al (2008), who specifically recruited for maximum variation, ensuring that the sample was proportionally diverse for both demographics and experience. Cultural differences could have affected the interpretation of some results. Isbir and Mete (2013) recruited from a metropolitan city in Turkey, while Chou et al (2006) conducted face-to-face interviews with 10 purposefully sampled Taiwanese women experiencing mild to moderate NVP. The remaining samples were from Western societies. Reflexivity and/or field journaling by the authors was generally lacking; a feature which, given the well-documented stigma and misconceptions surrounding HG, would add strength to research in this field (Dean, 2016). There are two exceptions to this: Meighan and Wood (2005) and Munch (2002b), both of whom use journaling as strategies to increase trustworthiness.

Synthesis of the data and development of themes

A summary of the findings and the identified themes were extracted (Table 1) and coded for analysis. As new descriptive themes emerged, the data were analysed iteratively using the constant comparison method. Contrary evidence was sought and a table matrix developed to locate cross-study themes.

Results

A number of negative themes emerged across the publications. None of the studies reported positive aspects of HG, although Locock et al (2008) and O'Brien and Naber (1992) both reported women with ‘morning sickness’ saw nausea as a positive sign and that it was particularly welcome in women who had previously experienced miscarriage or stillbirth. However, despite nausea being expected, and even welcomed, participants were surprised by how unpleasant it was. Four main themes, directly related to mental health and wellbeing, emerged from the studies; they addressed the depth and breadth of the effects NVP and HG had on participants. These are: social isolation; unable to care for self and others or change of role; negative psychological effects (depression, anxiety, guilt and loss of self); and sense of dying, suicidal ideation or termination. A further two subthemes, indirectly related to mental health and wellbeing, were found: loss of earnings or employment and changes to family plans. The occurrences of each theme per study are identified in Table 2.

| Study | Social Isolation | Unable to care for self and others, change of role | Negative psychological effect, guilt and loss of self | Sense of dying, suicidal ideation or termination | Loss of earnings or employment | Change to family plans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O'Brien and Naber (1992) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| O'Brien et al (1997) | ✓ | |||||

| Munch (2002b) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| O'Brien et al (2002) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Meighan and Wood (2005) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chou et al (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Locock et al (2008) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Power et al (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Isbir and Mete (2013) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Social isolation

Social isolation was a theme in seven of the studies reviewed (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; O'Brien et al, 1997; Munch, 2002b; O'Brien et al, 2002; Meighan and Wood, 2005; Chou et al, 2006; Isbir and Mete, 2013). Three key causes of isolation emerged from the review. In five studies, isolation was described as a self-imposed strategy to manage symptoms that were exacerbated by sensory stimulation and movement, yet loneliness occurred as a result (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; O'Brien et al, 1997; O'Brien et al, 2002; Chou et al, 2006; Isbir and Mete, 2013). Fear of public vomiting, and the humiliation that would cause, was another reason for isolation (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; O'Brien et al, 2002; Meighan and Wood, 2005; Chou et al, 2006). Three studies found that women isolated themselves to avoid negative responses from other people who questioned the reality or severity of their illness (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; Munch, 2002b; Meighan and Wood, 2005). Munch (2002b) highlights this with the following quotation:

‘As far as other women in the public and other people, they think it's all in your head, and they don't understand why you're so sick. Because they weren't sick, they think you're just weak.’

Inability to care for self and others; change of role

Seven studies found some women reported not being able to perform self-care activities due to an exacerbation of symptoms caused by activities such as showering (Chou et al, 2006), brushing their teeth and hair, getting dressed (Isbir and Mete, 2013), eating or preparing food (O'Brien et al, 2002; Meighan and Wood, 2005), or even standing up unaided (Power et al, 2010). These adverse effects seem substantial, yet are often mentioned only briefly in comparison to the effect of women's inability to look after their families. Failing to complete chores such as cooking for their husbands or housework tasks was mentioned by multiple women in five studies (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; Munch, 2002b; O'Brien et al, 2002; Meighan and Wood, 2005; Isbir and Mete, 2013).

Childcare was a pressing issue for women in four studies and was linked closely with themes of changes to family plans and feelings of guilt (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; O'Brien et al, 2002; Locock et al, 2008; Isbir and Mete, 2013). Munch (2002b) further discusses the incompatibility between the expectations of women to continue their daily roles of mother, wife, employee and the reality of a severely debilitating illness. She posits that the unrealistic expectations are due, in part, to the belief that HG is not an illness but a normal part of pregnancy; a theory supported by O'Brien and Naber (1992), Power et al (2010) and Isbir and Mete (2013).

Negative psychological effects (depression, anxiety, guilt and loss of self)

All but two studies (O'Brien et al, 1997; Chou et al, 2006) discussed the far reaching, and often profound, negative psychological effects of severe NVP and HG. Furthermore, despite historic suggestions of a psychological aetiology for HG, a number of participants in these studies emphasised that the negative psychological sequelae were an effect of NVP or HG rather than cause. As Power et al (2010) stated:

‘The women were in no doubt that their emotional problems were a result of nausea and vomiting and not a cause of it.’

Munch (2002b) specifically looked at causal explanations for HG, finding that stress resulted from HG rather than caused it; women made statements such as ‘I wasn't stressed until I got sick’ (Munch, 2002b: 67). The findings indicated a cycle whereby the physical symptoms and emotional responses became intertwined and exacerbated.

O'Brien et al (2002) described ‘loss of self’ and ‘feelings of guilt due to helplessness’ as the worst effects of HG. One source of guilt described was the inability to fulfil pre-conceptual roles and a sense of responsibility for the severity of the condition. The loss of self was intrinsically intertwined with all other facets of the condition, as one woman described:

‘I stay at home and it's between my bed and my rocking chair and the toilet and that's basically what my life consists of.’

Locock et al (2008) explained this loss of self as the sort of ‘biographical disruption’ described by people with chronic illnesses. While they acknowledged that, unlike chronic illness, NVP and HG are transient and time-limited, they suggested that adverse effects may be heightened when women's identities were already undergoing a process of redefinition and uncertainty due to the pregnancy itself.

Sense of dying, suicidal ideation or termination

Discussion of terminating the pregnancy occurred in four studies (O'Brien et al, 2002; Meighan and Wood, 2005; Chou et al, 2006; Isbir and Mete, 2013), although it was not the only method of ending the illness that was identified. Meighan and Wood (2005) interviewed eight women who had experienced HG and found most women considered various options for ending the illness. One woman considered termination, another repeatedly asked doctors to induce labour early to end the sickness, and others mentioned the possibility of their own death; either fearing it or wishing for it. Morbid thought and suicidal ideation was not unique to Meighan and Wood (2005). O'Brien and Naber (1992), O'Brien et al (2002), and Power et al (2010) all explored cases of women thinking they were dying or wishing to die. O'Brien et al (2002) illustrated the phase of illness they described as ‘Annihilation’ with the following quotes:

‘I want my life back; I am dying; I felt really not alive. It's like I really don't exist anymore, and I am hyperemesis.’

‘It was so bad I was even thinking about getting an abortion because I couldn't endure it anymore … I thought, “This is not worth killing myself over.”’

One woman in the study by Isbir and Mete (2013) expressed a desire to terminate her pregnancy, despite religious belief condemning abortion, and described the additional struggles such conflict invoked; whereas a woman in the study by Chou et al (2006) described strong family support as the reason she avoided terminating the pregnancy.

Loss of earnings or employment

Given the inability of women with HG to care for their homes, families and self, it is unsurprising that employment was affected and, women in three studies reported financial hardship (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; Munch, 2002b; O'Brien et al, 2002). Munch (2002b) provided the richest discussion of employment, again expressing surprise at employers' expectations that women will work despite a debilitating illness:

‘In fact, my office called because I couldn't come to work for a couple of weeks and told me that if I wanted my job I better get back to the office.’

Changes to family plans

A number of women in three studies state that they do not want more children due to HG. Four of the five HG diagnosed women in O'Brien and Naber (1992) state they would not plan or welcome another pregnancy. Women in both Meighan and Wood (2005) and Locock et al (2008) supported this, with a participant in the later explaining their decision thus:

That was another big factor in deciding not to have any more, because I thought I cannot even imagine having to look after a child when you're feeling like this.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

All the studies were limited by a lack of diversity with a dominance of married women from higher than average socioeconomic status within their populations; with the exceptions of Munch (2002b) and Locock et al (2008). It seems likely that pre-existing psychosocial or financial stressors would amplify the adverse effects of HG. While the diversity in the samples is no small concern, the publications themselves offered some demographic diversity, with research from the US (O'Brien and Naber, 1992; Munch, 2002b; Meighan and Wood, 2005), Canada (O'Brien et al, 1997; O'Brien et al, 2002), Taiwan (Chou et al, 2006), Turkey (Isbir and Mete, 2013) and the UK (Locock et al, 2008; Power et al, 2010). However, there remain entire parts of the globe that are not represented.

The earliest included study dated back to 1992 and good quality research has been consistently published until the most recent of the included studies. All studies provided in-depth descriptions of the immediate and profound ways that NVP and HG affected the lives of women and their families; however, there was a lack of discussion regarding long term effects on women's mental health. A number of the excluded publications and other literature (Poursharif et al, 2008; Christodoulou-Smith et al, 2011; Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017) alluded to severe long term mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, but the quality of the evidence was lacking. This is an area that warrants further investigation.

This review was not limited to women with HG and specifically included women with milder levels of NVP. As discussed above, there is not yet an internationally agreed definition of HG as a distinct condition from moderate or severe NVP, nor are there clinical categories of severity of NVP. This means that making such distinctions in research is problematic (Grooten et al, 2016). By including women with a range of experiences, this review highlights the negative effects that can occur for women across the spectrum. While effects maybe increased for those experiencing HG, those without a clinical diagnosis of HG may suffer adverse psychosocial effects from symptoms. For example, one participant in the study by Chou et al (2006), who specifically excluded women diagnosed with HG, considered terminating her wanted pregnancy due to the severity her symptoms.

The majority of studies reviewed are somewhat dated, which may reflect a lack of recent high quality qualitative research into the effect of NVP and HG. Despite this, the studies included remain culturally relevant in their contexts. The lack of diversity and global representation as discussed above is also a limitation and additionally reflective of the paucity of international qualitative research into NVP and HG. As with most qualitative research, results from this review may not be generalisable to wider populations and women's experiences of severe illness will vary for individuals.

Areas for further research

Given that infertility has been well established to have a negative long-term psychological effect on women, men and couples (Luk and Loke, 2015), it seems reasonable that other reproductive obstacles, such as a medical condition in pregnancy, could have a similar effect. This review suggests that women's reproductive choices and planning were adversely effected by HG; findings supported by other authors (Poursharif et al, 2008; Dean, 2014). However, there is a paucity of high quality qualitative research addressing how parents' plans are affected by the probability of HG recurring. How HG affects women who already have children and their families is also not sufficiently addressed in this review, and there is a clear need for further research into this specific area. In their exploration of women's experiences of terminating a pregnancy due to HG, Dean and Murphy (2015) found that the stress of childcare and inability to care for their families was a major reason for women terminating otherwise wanted pregnancies. The report suggested that the grief following termination was comparable to that expressed by couples who underwent abortion for congenital abnormalities, and could persist for many months or years. Further qualitative exploration of such experiences would be highly valuable.

Social isolation, lack of supportive relationships and stressful life events, such as illness, are established risk factors for peri- and postnatal depression (Hammond and Crozier 2007; Husain et al, 2012). The literature presented here did not always make a direct link between the individual effects and a negative mental health outcome; however, the accumulation of risk factors (such as social isolation, financial worries, employment vulnerability) is likely to have a snowball effect, as many of the women experienced multiple effects from HG.

Suicide is the leading cause of maternal death in the 12 months postpartum (Knight et al, 2016). Given the number of papers identifying morbid thought and suicidal ideation among their participants, this is of particular concern and needs rapid further investigation.

Clinical implications

As discussed earlier, there remains a persistent stigmatisation of HG, in part due to psychiatric aetiology theories, which can affect the care and treatment that women receive (Dean, 2016). Arguably, whether mental ill health is a cause or a result of HG should not alter the quality of care. Increasing awareness among health professionals, and indeed the public, of the biological origin and psychological response may help to break down such stigma (Mitchell-Jones et al, 2017). Reassuring women that it is understandable to feel depressed and anxious when experiencing such extreme symptoms, thereby validating their experience, is likely to be reassuring (Kim et al, 2009).

Understanding the myriad effects that NVP and HG has on women and their family's lives may help health professionals to develop an empathetic appreciation of the psychological burden. The clinical approach may also shift to holistically encompass the extensive biopsychosocial effects. Kim et al (2009) suggest a number of approaches for helping women with HG, allowing women to express the physical and emotional distress, frustration and disappointment they are feeling and validating their feelings. They recommend that practitioners do not attempt to connect the stress and physical symptoms initially, but rather try to strategise how stress can be reduced, for example by family members relieving women of daily responsibilities.

Assessing a women's support network, or helping her to establish one, may be of practical benefit. Kim et al (2009) suggest educating a woman's psychosocial support network regarding the biological nature of the condition and stress responses to severe illness. Professionals can also refer women to charities, as recommended by the UK Green-top Guidelines (RCOG, 2016) (Box 1).

Additional strategies to reduce the burden include: planning outpatient or at-home rehydration services so as to reduce familial disruption; an aggressive approach to anti-emetic therapy to control physical symptoms; providing information about the condition and, where appropriate, referral to perinatal mental health services (RCOG, 2016).

Conclusion

This review highlights the diverse and profound effects NVP and HG can have on a woman's life, which can negatively affect their mental health. Social isolation is known to be a major risk factor for postnatal depression; this review demonstrates that for women with severe NVP or HG, social isolation can begin in early pregnancy and may persist throughout. Pressures to maintain roles as mothers, wives and employees contribute to stress and anxiety. Associated with NVP and HG are morbid thought, suicidal ideation and termination of otherwise wanted pregnancies. Whether the psychological morbidity ends when the physical symptoms end is yet to be satisfactorily explored, but it is likely that mental ill-health persists beyond the end of the pregnancy.

Health professionals need to be aware of the effects this debilitating condition can have on women's lives so that treatment can be planned holistically. They can help by voicing and validating feelings of psychological distress and referring appropriately for support.